Case 1.5 – Emergency Anaesthesia (Airway Management)

Case

The orthopaedic registrar calls to book a 25 year old male for an Open Reduction Internal Fixation (ORIF) of a compound fracture of right distal tibia and fibula sustained in a motorbike accident (MBA). He is concerned that the vascular supply is compromised as distal pulses are weak. The patient also has facial lacerations including to his upper lip that require a compound scrub and repair. Both leg and facial wounds are heavily soiled and the surgeon would like to proceed as soon as possible.

The patient had been drinking alcohol prior to the accident and had a blood alcohol content of 0.07 on presentation 1 hour ago. He is not known to have any past medical history, states no known allergies and is a current smoker.

The orthopaedic registrar has since cleared his cervical spine of injury and removed the hard collar.

He has had a total of 20mg of morphine over the past 1.5 hours.

Questions

Owing to the nature of this patient's injuries, his surgery cannot be delayed to allow appropriate fasting (and sobering up) time to elapse. Prompt exploration of the wound may restore the vascular supply and prevent ischaemic damage to the distal tissue. Expediting debridement of soiled and devitalized tissues is key to minimizing infection risk.

The anaesthetist should perform the usual pre-anaesthetic assessment including history, examination and review of investigations. In urgent trauma cases, the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) system provides a comprehensive framework for simultaneous diagnosis and management. The anaesthetist should review the workup undertaken so far by the Emergency Medicine team.

Primary Survey as per ATLS Guidelines

- Airway maintenance with cervical spine protection

- Breathing and ventilation

- Circulation with haemorrhage control

- Disability: Neurologic status

- Exposure/Environmental Control: completely undress patient but prevent hypothermia

Secondary Survey

History:

- Allergies

- Medications currently used

- Past illness/Pregnancy

- Last meal

- Events/Environment related to injury

Physical Examination: head to toe examination including logroll, perineal region PRE +/- PVE "fingers and tubes in every orifice"

Investigations: ECG and trauma series of x-rays + further imaging, ABG's, pregnancy test, toxicology screen as indicated

Additional information relevant to the anaesthetist:

History of presenting complaint:

- (1) Nature of MBA: speed, combatant (eg. car, tree), point of impact (eg. thrown onto road), protective clothing (eg. presence of helmet, leathers), state on scene and in transit

- (2) Alcohol and other intoxicant intake including quantity and time frame

- (3) Background medical, surgical and anaesthetic history, smoking, alcohol use, medication, allergies and fasting status

Examination - Special attention to:

- (1) General status: distressed, intoxicated, altered conscious state, co-operative, hydration, observations, ability to consent

- (2) Airway assessment: Perioral and other facial lacerations hint at cervical spinal trauma, intra-oral trauma including broken teeth, tongue or mucosal lacerations which add to airway difficulties (unstable cervical spine, aspiration of tooth fragments, stomach full of swallowed blood, swollen tongue)

- (3) Potential occult injuries

- Alcohol intoxication

- Not fasted

- Trauma, pain

- Blood in airway

- Recent opioid administration

His airway management will be difficult because of:

- High aspiration risk

- Perioral lacerations may limit mouth opening or impede mask seal

- Potential blood in airway, intraoral lacerations or swelling

The patient's background risk of airway difficulty must be taken into account with the usual assessment of indicators such as Mallampatti score etc.

To optimize the patient's preparation:

- Explain the procedure and allay anxiety

- Prokinetic agent to empty stomach

- Ensure optimal positioning

Equipment required includes an anaesthetic delivery system, suction and monitoring, an appropriately sized face mask, size 3 and 4 Mackintosh laryngoscope blades with a light source handle, a variety of sizes of cuffed endotracheal tubes, a stylet and bougie and 10 ml cuff syringe. The difficult intubation trolley should be in the room to allow access to airway devices, such as Guedel airways, LMA's, bronchoscopes and alternate laryngoscope blades. All equipment must be checked for function and within easy reach as once your assistant applies cricoid pressure, he/she cannot leave to fetch other equipment.

In the case of a suspected difficult airway, the plan for management should be clearly communicated to the operating theatre team. Your assistant should be clear on your initial plan (Plan A) for management and the fallback positions if this fails (Plans B and C etc).

This patient will require a rapid sequence induction for endotracheal intubation.

The principles of this are:

- Preoxygenation

- Optimal patient position

- Application of cricoid pressure on induction

- Rapid intubation to secure the airway

- Avoidance of bag-mask ventilation

- Use of short-acting agents that allow return of spontaneous ventilation in an acceptable time frame if ventilation and airway control is not possible

If the larynx is unable to be intubated despite appropriate manoeuvres, bag and mask ventilation should be instituted and a decision taken whether to awaken the patient or maintain anaesthesia. Many algorithms exist to assist with this decision making process, including this from the Difficult Airway Society.

If the larynx is unable to be intubated despite appropriate manoeuvres, bag and mask ventilation should be instituted and a decision taken whether to awaken the patient or maintain anaesthesia.

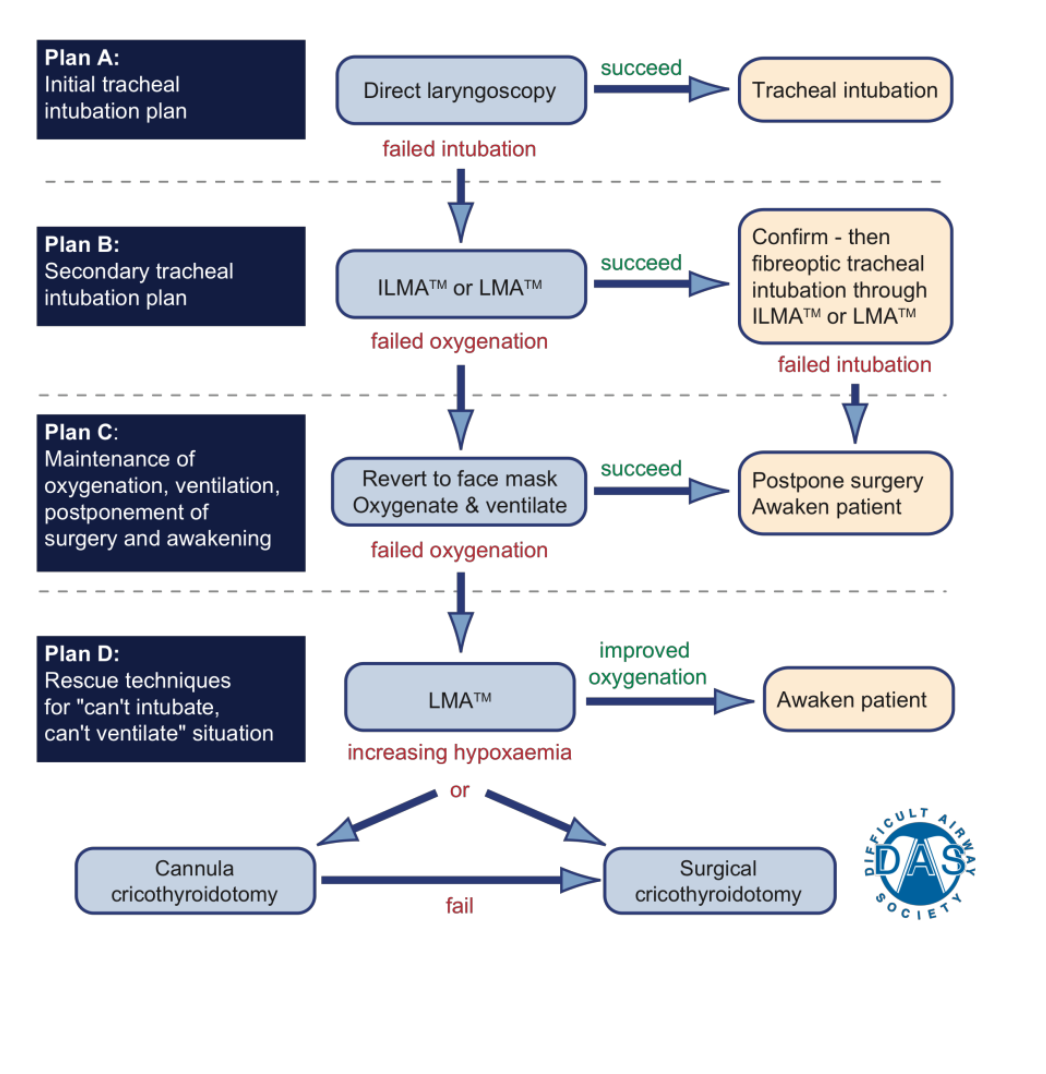

The Difficult Airway Society provides the following algorithm for failed intubation management:

Key principles of failed intubation planning:

- Plan A: Initial tracheal intubation plan - Direct laryngoscopy

- Plan B: Secondary tracheal intubation plan - ILMA™ or LMA™, followed by confirmation via fibreoptic tracheal intubation through ILMA™ or LMA™

- Plan C: Maintenance of oxygenation, ventilation, postponement of surgery and awakening - Revert to face mask, Oxygenate & ventilate, leading to either Postpone surgery/Awaken patient or continue to Plan D

- Plan D: Rescue techniques for "can't intubate, can't ventilate" situation - LMA™ (if not already attempted), which may lead to either Awaken patient or proceed to Cannula cricothyroidotomy or Surgical cricothyroidotomy

The algorithm emphasizes that at each stage, oxygenation is the priority. If one plan fails, move to the next plan. The ultimate rescue is a surgical airway (cricothyroidotomy) if all other measures fail and the patient cannot be oxygenated.