Case 1.1 – Pre-operative Anaesthesia Assessment (Low Risk)

Case

Harry is a 53 year old man who presents to the Anaesthetic Clinic for assessment prior to his elective left knee arthroscopy. His knee is painful, particularly at the end of the working day, and is intermittently swollen and hot.

Booking observations are: T 36.6; BP 120/80; PR 84reg; RR 16; SpO2 97% in RA

His medical history includes treated hypertension and gout. He is an ex-smoker, ceasing 10 years ago, and has an average of 5 standard alcoholic drinks per week.

His medications are amlodipine 10mg mane and allopurinol 300mg mane.

Questions

The goal of pre-anaesthetic assessment is to formulate an anaesthetic plan, establish rapport with the patient and obtain informed consent. History, physical examination and review of investigations helps identify for each individual case the patient, anaesthetic and surgical factors that will influence the selection of optimum anaesthetic technique and peri-operative care.

To achieve this, one must know:

- (i) The state of the patient presenting

i.e. features of the presenting complaint and background co-morbidities - (ii) The surgical requirements for the case

e.g. muscle relaxation, PPV, prone positioning, emetogenic procedure etc. - (iii) The relevant anaesthetic issues

e.g. known or anticipated difficult airway management, history of post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV), history of malignant hyperthermia etc.

Let's look in detail at Harry's case:

HISTORY

Presenting complaint: non-specific knee pain for investigation, likely osteoarthritic in nature. No evidence of generalized sepsis on observations.

Past Medical History: treated hypertension with acceptable booking BP, history of episodic gout

Further information can be gained by enquiring specifically about adequacy of BP control and potential end-organ consequences. For example, "Is your GP happy with your blood pressure?" "Has your dose of antihypertensive been changed recently?" "Have you ever had any complications related to BP control, such as problems with your heart, kidneys or a stroke?"

Systems review should enquire about key conditions affecting the major organs/systems. Questions should be broad initially:

- "Have you ever had any problems with your heart, a heart attack or angina?"

- "Do you have any chest or lung complaints, asthma or emphysema?"

- "Have you ever had any, strokes, fits or turns?"

- "Do you have diabetes?"

- "Do you suffer from indigestion, heartburn or gastro-oesophageal reflux?"

- "Have you ever had any problems with your liver or kidneys in the past?"

Further detailed questioning will follow as indicated.

Move on to questioning about smoking and alcohol intake, allergies/adverse drug reactions and current medications including non-prescription or complementary therapies.

Knowledge of fasting status is essential.

Past Surgical History: may reveal problems with previous anaesthetics. It is critical to ascertain a history of issues such as allergic reactions, airway difficulties, awareness under anaesthesia or malignant hyperthermia. A positive family history for "problems with anaesthetics" should be explored as this may represent malignant hyperthermia or delayed recovery from suxamethonium.

EXAMINATION

Airway examination is commonly the first step. A number of key anatomical assessments are made to help gauge the ease or difficulty anticipated in managing the patient's airway.

These include:

- General assessment: body habitus, resp distress, on oxygen therapy, stridor, scarring or pathology of the head and neck

- Mouth opening and interdental distance

- State of dentition: poor dental health, loose teeth, protruding, prostheses or dentures

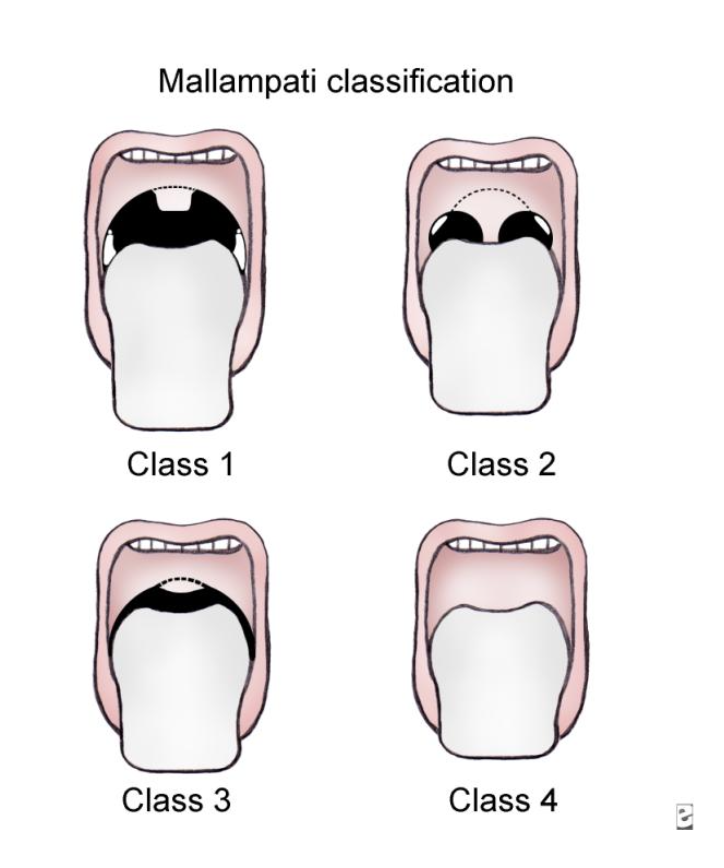

- Mallampatti score: appearance of the posterior pharynx with mouth open and tongue protruding can predict difficulty visualising the larynx at laryngoscopy

- Mandibular size and TMJ function

- Thyromandibular distance

- Cervical spine range of motion

Further physical examination should be focussed on the cardiac and respiratory systems, with other systems emphasized as indicated by the patient or the case. For example, in a patient having a carotid endarterectomy it would be prudent to document any pre-existing neurological deficits prior to anaesthesia.

INVESTIGATIONS

Ordering investigations should be guided by the features of both the patient and the proposed surgery.

General principles include:

- Baseline full blood count (FBC), urea and electrolytes (U and E's) for older patients having moderately invasive procedures, particularly on medication for cardiovascular disease (eg diuretics that can cause electrolyte disturbances)

- Coagulation profile and group and hold if bleeding diathesis (innate or therapeutic) or procedure associated with potential significant blood loss

- Liver function tests if history suggestive of hepatic dysfunction

- Pregnancy test if possibility of pregnancy, particularly with gynaecological surgery

- ECG routine for males >50years, females >60years, and for any patient with history of cardiovascular disease or arrhythmia

- CXR if history of cardiovascular or respiratory disease, or malignancy

- Respiratory function tests (including peak flow measurement, spirometry pre- and post-bronchodilation and lung volume/diffusion capacity evaluation) if significant respiratory disease, particularly recent acute exacerbation

- Non-invasive and Invasive cardiac investigations: see question 2

Therefore, in Harry's case it would be reasonable to request FBC and U and E's, and an ECG. One could argue as an ex-smoker with treated hypertension that a CXR may be warranted, but in the absence of any history suggestive of respiratory compromise or cardiac failure, it would be unnecessary.

Assessment of exercise tolerance gives clues to the patient's cardiorespiratory reserve. It is assessed by convention using a metabolic equivalent scale (see table below). Patients unable to meet the demand of four metabolic equivalents (4METs = climbing a flight of stairs) are considered to have minimal cardiorespiratory reserve and at high risk of perioperative cardiorespiratory compromise. Sometimes patient's exercise tolerance is limited by other conditions, such as back pain or claudication, such that history alone is inadequate to assess cardiac reserve. These patients may require further non-invasive or invasive cardiac testing such as stress echocardiography or coronary angiography.

Exercise tolerance also gives clues to the degree to which the patient's presenting complaint is impacting on their life and their ability to care for themselves post-operatively. These factors are important for assessing suitability for ambulatory (or day-case) surgery, discharge planning and the ultimate suitability of some procedures for individual patients.

| Level | Activity |

|---|---|

| 1 MET | Can you... Take care of yourself? Eat, dress, or use the toilet? Walk indoors around the house? Walk a block or 2 on level ground at 2 to 3 mph (3.2 to 4.8 kph)? |

| 4 METs | Do light work around the house like dusting or washing dishes? Can you... Climb a flight of stairs or walk up a hill? Walk on level ground at 4 mph (6.4 kph)? Run a short distance? Do heavy work around the house like scrubbing floors or lifting or moving heavy furniture? Participate in moderate recreational activities like golf, bowling, dancing, doubles tennis, or throwing a baseball or football? |

| Greater than 10 METs | Participate in strenuous sports like swimming, singles tennis, football, basketball, or skiing? |

In Harry's case it would be reasonable to request:

- FBC and U and E's - baseline assessment for older patient having moderately invasive procedure, particularly on medication for cardiovascular disease

- ECG - routine for males >50years, and he has history of treated hypertension

One could argue as an ex-smoker with treated hypertension that a CXR may be warranted, but in the absence of any history suggestive of respiratory compromise or cardiac failure, it would be unnecessary.

Aspiration is the passage of liquid or particulate matter from the upper airway into the trachea and lower respiratory tract. This can result in physical obstruction of large and small airways as well as chemical pneumonitis. Both conditions impair ventilation and gas exchange, and can lead to pneumonia.

Risk of this occurring increases with:

- Impaired airway protective reflexes

- Depressed level of consciousness

- Vomiting or regurgitation

- Trauma/bleeding in the airway

- Delayed gastric emptying: gastroparesis, recent opioid administration

- Incompetent lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS): GORD, hiatus hernia

- Increased barrier pressure at the LOS: obesity, pregnancy, ascites

- Recent ingestion of food

Aspiration risk should be assessed for each patient. Appropriate fasting times for elective surgery are:

- Solid food, including milk and infant formula – 6 hours

- Breastmilk – 4 hours

- Clear liquids – 2 hours

Regular medications are taken with a small sip of water as advised by the anaesthetist. Fasting patients should abstain from chewing gum or suck lollies as this can stimulate increased gastrointestinal secretions.

Aspiration risk can be minimized in elective surgery by pre-medication with appropriate duration of fasting, motility agents to enhance gastric emptying, proton pump inhibitors and antacids to raise gastric pH, attention to patient position and airway management.

Cigarette smoking results in:

- Increased blood concentration of carbon monoxide (CO) which reduces the oxygen carrying capacity of the blood

- Blood nicotine concentration increases BP, myocardial contractility and HR and causes peripheral vasoconstriction

- Hypersecretion of airway mucus, impaired tracheobronchial clearance and airway irritability

- Smokers' polycythaemia, increased blood viscosity and hypercoagulable state

These changes contribute to a higher risk in smokers of respiratory complications and poor wound healing.

Blood levels of CO and nicotine improve within 12-24 hours of abstinence. Sputum production will initially increase for 1-2 weeks following smoking cessation, but declines within 4 weeks. Hypercoagulable state can take 2-14 days to reverse potentially increasing the risk of venous thrombosis.

Post-operative respiratory complications have not been shown to decrease until 6-8 weeks. Current recommendations suggest patients should be encouraged to cease smoking 6-8 weeks prior to surgery, or abstain from smoking for at least 12 hours before operation.